Curriculum and jiu jitsu: Designing an Effective Program

A discussion on important things to consider when designing curriculum for jiu-jitsu.

Note: This article is also available as an episode of Punchsport Pagoda. This is simply the written version of that episode.

Preamble Ramble

Today I’m going to talk to you about some important concepts when it comes to designing a jiu jitsu curriculum. This is a thing I think its quite important and worth having a discussion on. Now, currently I have this written out as one episode but there may be a few more I make on similar or related topics.

Before we get into the deeper focus on this topic I should probably explain how and why I think I have some role to play in this conversation. I’ve been doing jiu jitsu for the better part of a decade and one of the It’s also a sport where there is an evolving and ever changing meta, which in turns requires knowledge to be generated and passed along. Furthermore, I’m actually in the process of working on my PhD thesis in Educational Research so it’s not very surprising to know that I’m quite interested and well read on education related topics.

I like to blend the two and in some of my previous written work I’ve done just that. I’ve taken MMA and jiu jitsu and talked about them from the lens of an educator as I think those areas are often not commonly brought up or discussed.

That’s not for any special reasons, just that it’s an often overlooked and under-discussed aspect of the sport.

One of the most important things you can find in the jiu jitsu landscape is the need for, and management of, a good curriculum. This is something I have personally observed, as well as friends and training partners expressing in our conversations at the gym. This specific point is often mentioned as one of the more important indicators that you’ve found a good coach. Do they have a curriculum or do they just wing it after watching a five-minute video on YouTube?

I’ve had both kinds of coaches and learning environments and speaking from my own experience, someone taking the time to figure out a curriculum is going to be way better to learn from not just in terms of technical knowledge, but holistic development of your jiu jitsu game.

Which brings me to today’s article. While I was in grad school I was tasked with writing a relatively short paper that analyzed a curriculum in any setting I chose and looking at what the academic outcomes were, as well as what misalignments occurred.

I took a recent look at the papers and thought they’d be worth discussing. Now, I want to emphasize that this is not going to be a step-by-step breakdown of how to make a curriculum. Instead, the focus here is on the overarching approach and key concepts to designing a well-rounded curriculum. This is a very academic focused discussion and more so sits in the realm of the heady concepts that govern educational work, more so than jiu jitsu itself or how to be a good coach. To that last point, these sorts of discussions are how I think you can improve as a coach but again focusing more on education skills rather than how to do a flying gogoplata well. In short, this is the stuff you need to know to make sure your curriculum is achieving what you want it to achieve and how to assess your curriculum.

This analysis we’re going to go through specifically looks at the kids jiu jitsu program I had to design and conduct while teaching a kids jiu jtisu class in South Korea.

So, without wasting too much time on the preamble, let’s get into it.

Background of the Analysis

Here’s the quick and simple background to help set the stage for understanding the purpose and reason this curriculum we’re looking at.

I was training at the main Alliance affiliated gym in South Korea, where I also happened to be the only non-Korean. For the most part, there were some other non-Koreans who would show up and train for a bit and then move on.

In 2019 I was approached and took on the job of creating and conducting a 16-week jiu jitsu program for South Korean kids aged 5 to 10. The basic guidelines were that these kids would have no prior experience with jiu jitsu and there was no current or available curriculum I could use.

To that latter point, this branch of Alliance did not have a prior kids program to build a curriculum off. Additionally, while Alliance does have their own internal curriculum at the time I did not have access to it, so I was left designing my own curriculum.

So, the main learning goals that we have for the kids in the program were as follows:

Teach basic jiu jitsu techniques

Help them develop body control

Foster teamwork and discipline

And, this one would be the biggest challenge, teach the classes in English to a bunch of non-English speaking kids to support their language learning and encourage English development and usage.

That last goal was also pretty much the main learning outcome the parents were expecting and why the whole program existed.

South Korea has English as a mandatory language; however not all South Koreans are as proficient in English. So, the goal here was to help support and further the English language development the students were getting at their public schools by exposing them to English in a new environment. This is not too uncommon in South Korea and so that was why I the lone non-Korean at the gym was tasked with heading up the program.

To say this was a challenging task is an understatement.

Terminology to Keep in Mind

Now, before we start, I think it’s important to clarify some terminology.

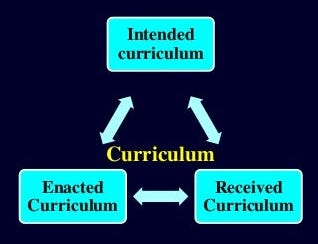

When I say “curriculum” I’m not just simply meaning the list of things to teach. Researchers Gobby & Walker explain that a curriculum is the course’s contents being learned by the student and being taught by the instructor. They state that this summarization is a very narrow view and that there is much more nuance and breadth to the concept of curriculum than what is commonly assumed. Furthering this discussion of what exactly curriculum is, the researchers Webster & Ryan (2019) also state that there are multiple types of curriculum. These most typically are seen as; intended (stated), enacted, experienced, null, hidden, learned, and assessed.

For the purposes of the analysis of the curriculum I designed and today’s discussion we’ll focus on three: intended curriculum, enacted curriculum, and experienced curriculum. That is not to say the other forms are not necessary, but once we started talking about just these three and how they interrelate you’ll start to realize how thick into the weeds we get. And this is just a surface level discussion.

To simply describe these curriculum types, let’s put them in the context of a jiu jitsu setting.

The intended curriculum takes the form of the specific learning outcomes, aka what you want your student to know at the end of a session. This, in jiu jitsu terms, are the techniques or system of techniques that you can teach in a set order or chain so your student can repeat them while sparring or competing. So again, the intended curriculum is WHAT YOU WANT THEM TO LEARN.

Next, the enacted curriculum is what is being taught by the educator during the period of learning. This is less about the specific topics, but how those topics are taught and the way they are taught. Enacted curriculum is quite closely linked to pedagogical approaches and so if you’re aware of at least what pedagogy is, then you’re already about halfway there to understanding this concept. Again, enacted curriculum is WHAT IS BEING TAUGHT AND HOW.

Finally, we have the experienced curriculum. This is, probably, the biggest one of the three to be mindful of. Experienced curriculum is described as being what is actually experienced by the student as they engage with what is being taught. This term applies regardless if the experience is happening in a planned or unintended manner. When we apply this to jiu jitsu, you can see it in the form of your students developing a sense of understanding on timing, positional placement of body parts, knowing when to or not apply pressure, and so forth as they are completing a technique you taught. Furthermore, this can also apply to the psychological state of the learner, in the context of a jiu jitsu program this can be seen when a student is able to maintain focus during a competition after the experiences of sparring and competing over time, as compared to when they first start. To simplify this, experienced curriculum is ultimately WHAT DID THE STUDENT TAKE AWAY FROM THE LESSON?

So we have these three curriculums:

Intended, what we’re are trying to teach.

Enacted, what and how we are teaching the topic.

Experienced, what is gained and retained by the student.

All of this is to say that curriculum as a concept is far more nuanced than you may initially think it is. Curriculums are entire ecosystems of learning where these various parts all interact and affect each other in nuanced and subtle ways.

So now that we have these three terms, let’s dive a bit deeper into this curriculum program and how these curriculum types come into play.

Let’s Analyze this Program Already

In the case of the program I created and taught at Alliance Korea, the newly created intended curriculum was planned to focus on in person training sessions for two hours per week over the course of a 16 week long schedule that would then repeat itself. The course aims were shaped by what the head coach at Alliance Korea viewed as the base standards for jiu jitsu learning. So, the program was designed along “normative needs”, as described by Morrison et al, by using the established IBJJF requirements for belt promotion for children, as well as the standards outlined by Alliance Jiu Jitsu itself.

Having autonomy in the design, I was allowed to utilize external curriculums from other children’s programs for jiu jitsu. In this case I relied heavily on the Gracie University Bully Proof program, which I think is quite good in general but there are some minor grievances I have with it that I won’t really get into today. In addition, I went out and got personal guidance via conversations with other coaches at different gyms around the world. Mostly these were my friends who I just knew from jiu jitsu and who happened to be teaching kids classes as well.

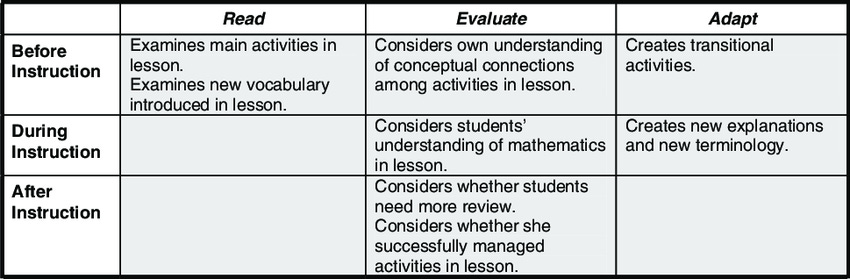

As the sole educator, it was my responsibility to track and maintain an understanding of the intended curriculum and effectively perform it during the learning sessions. Unbeknownst to me at the time, my preparation work for each of the training sessions for whole program followed the curriculum strategy framework as described by researchers Sherin & Drake in 2009. According to their framework, there are three phases of curriculum strategy; reading, evaluating, and adapting.

The first stage, reading, comes when the instructor reviews the written documents and goals as an overview and for details prior to instruction and during instruction. The evaluating stage comes when a teacher focuses on the target audiences’ needs when determining if the curriculum is appropriate. The third stage, adapting, occurs when the instructor creates, replaces, or omits components from the curriculum during the instruction.

This can be seen when, prior to each lesson, I would review the written curriculum to ensure I knew what the goals for the day were as well as the associated teaching methods I was planning to use. Then, I would determine which of the techniques being focused on would be most suitable using the knowledge I acquired from observing and assessing the student’s development and skills.

Finally, I would then adapt the curriculum for the day by typically adding additional steps to the learning process to ensure a more clear line of knowledge was established that did not necessarily exist within the written curriculum. This can be seen when I would repeat the technique being taught, but add in a bit more information or detail to it so any consistently observed mistakes can be corrected.

Additionally, in the course of conducting the classes it was unknown to me that the existence of curriculum potential existed and was being explored. This concept, described by Ben-Peretz (1990), states that there are a range of possibilities for learning that are inherent in the curriculum. Thus, curriculum potential refers to the opportunities of learning that a particular curriculum provides for students so that they can learn and grow.

This potential can be maximized by designing the curriculum to meet the needs and interests of the students, and by using a variety of teaching methods and assessment strategies to promote student engagement and participation. Due to the large language barrier that existed between the children in the program and me there was more curriculum potential that existed within the context of the jiu jitsu training as opposed to the English language learning. These jiu jitsu specific examples came in the form of the techniques and drills as they provided opportunities for the students to develop physical strength, flexibility, balance, and coordination as well as mental focus.

When it came to the light sparring, that was part of the curriculum so as to develop technique application against a resisting partner, it allowed for the students to apply the learned techniques in a dynamic and more real-world context and to expand the approach of using strategic timing to apply the technique. This in turn benefited the students when it came to the concept of the experienced curriculum.

Interaction Between the Curriculums

Now that we’ve gotten all of this initial discussion out of the way, we can now take a look at how these three curriculums interrelate, how they can align or misalign, and what in my program did or did not work.

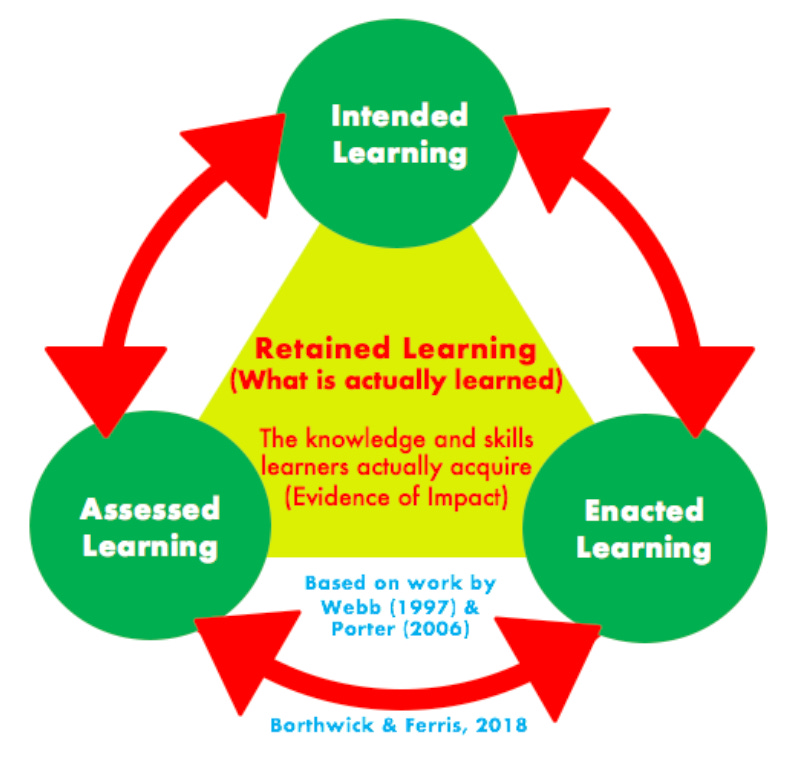

When looking at the curriculum it is important to assess the alignment of goals as stated in the intended curriculum to what is actually taught in the enacted curriculum.

According to Schubert (2008) there are opportunities for a misalignment to occur in the Intended-Enacted Curriculum relationship. Specifically, they mention that the differences in these two forms of curriculum can come from teacher misunderstanding in the form of reading the curriculum, evaluating the curriculum, or adapting the curriculum. This supports Sherin & Drake (2009) in their view of the intended-enacted curriculum relationship wherein educators can view, evaluate, or adapt a curriculum differently depending on various factors relating to the individual teacher.

In the case of the curriculum I designed, alignments and misalignments were seen in different areas. One such area of alignment was that the instruction of the techniques did follow the intended curriculum and its overall plan and approach to teaching technique sequences. As an example, the body mechanic known as “shrimping” was taught as a basic movement and a key necessity for the learners to develop and after the first lesson being exposed to it the children was able to competently perform the motion when needed.

However, when looking at the relationship a notable misalignment came in the form of the evaluation of the curriculum. Specifically, it was determined that the pacing of the introduction of certain body mechanic techniques was too fast and that the learners needed more time to develop proper balance and body control first. To resolve this issue, it became necessary to adapt the curriculum in its enactment to allow for more time to work on the nuances of the specific body mechanic motions and provide additional time for drilling.

Using the aforementioned curriculum strategy framework by Sherin & Drake (2009), this meant that the creation of new components to the curriculum were necessary, as well as omitting sections to fit within the allotted time for the lessons as well as within the total course program’s length. The results of this adaptation to the curriculum allowed the learners to get a better sense of the key foundational mechanics and techniques that would allow them to progress further with minimal impact later on in their development, rather than going down a path of poor technique performance and struggling to adjust at a latter point.

Another challenge with this alignment relationship was the issue of a language barrier existing between myself and the learners. As a native English speaker, one of the intended focuses of the program was to do all instruction in English to allow for exposure to the language for the non-English speaking learners. This goal was mostly met, but there were numerous instances of the learners clearly struggling to understand the instructions and directions that were given in English due to their own limited English capabilities. This would then cause misalignments in understanding the technique as effectively as a native English speaker could.

Thus, it became necessary to replace certain components within the intended curriculum, specifically terminology related to jiu jitsu, with more simplified and easier to comprehend terms. An example of this is rather than saying “use C grips”, the instruction had to be adjusted and the term “C grips” was replaced with “Lego hands.” This was a concept that was more readily familiar to the learner than the intended curriculum assumed, and so some adjustment and adaptation was needed.

The misalignment due to the language barrier does not solely exist within the realm of the intended-enacted curriculum relationship; rather it can also be seen in the enacted-experienced curriculum relationship as well. This second relationship refers to the degree in which what is actually taught and learned aligning with the experiences and understanding of the curriculum by the student. An example of this misalignment can come in the form of that pesky language barrier. As seen in the implementation of the curriculum, instructions were in a language that the children did not fully comprehend. Thus, at times they struggled to understand and execute techniques effectively. There was a clear lack of effective comprehension on specific body mechanics to perform techniques that caused the child to struggle executing them.

Another example of a misalignment was that some of the techniques appeared to be too difficult for some of the learners, specifically the younger ones, to properly perform likely due to lack of body control. There was visible frustration displayed by the learner when attempting to do the technique that led to them foregoing the proper methodology and instead performing a variation that ignored all the key foundational methods that were part of the instruction.

Despite these misalignments, there were also examples of proper alignment in the enacted-experienced curriculum relationship. This mostly came in the form of the students, during both sparring sessions and in competition, being able to perform several of the techniques they have been taught and had instruction on. There was also alignment between stated goals of the program when the students consistently showed good sportsmanship and behavior while at a competition by shaking their opponent’s hand win or lose. This indicates that there was successful alignment between the enacted curriculum and the experienced curriculum as the student ultimately portrayed a competent understanding of the lessons taught to them during the course of the kid’s jiu jitsu program.

Resolving Misalignments

Due to the existence of these misalignments across both relationships, it’s important to analyze and assess what alternatives could be used to adjust the overall curriculum to ensure there is no further deviation. One such solution to resolve any further issues with alignment can come in the form of a total reassessment and rewriting of the intended curriculum.

Due to the nature of the creation of the kid’s jiu jitsu program being that it was made with only guidelines from the head coach, further detailed instruction on what is or is not necessary would have been an ideal starting point. Allowing for the more experienced instructor to guide the creation of the curriculum could have negated any issues with introducing complicated concepts too early. This in turn may have lead to more focus on core fundamentals and development of those associated techniques that would have aided in the student’s ability to conduct body mechanics more efficiently.

Additionally, it would have allowed for a more refined approach towards teaching as the head coach had more jiu jitsu instruction experience whereas my own experienced drew from the realm of ESL classroom teaching. In conjunction with this, the choice of focusing on instruction being solely in English could have also been omitted from the curriculum to allow for better and clearer instruction to the students. There were several issues with the curriculum misalignment drawing from the reality that there was a large language barrier between the educator and the student.

There is also an argument to be made that emphasis on the curriculum not being about jiu jitsu techniques per se, but focusing on body movement and body mechanic exercises instead. Following the guidelines offered by the Canadian non-profit organization Sport for Life (2023) on long term athletic development of children, rather than focusing on highly technical mechanics associated solely with the sport of jiu jitsu. Instead, an emphasis could have placed on related body motions and control.

As there were issues with misalignment due to students struggling to effectively utilize required body mechanics and needing to develop those first, the focus on body mechanics would allow for better competency in the jiu jitsu specific techniques later on in their overall development. In conjunction with this, allowing for a division to exist splitting the classes up from a singular class covering the wide age range of 5 years-old to 10 years-old would aid in this endeavor and allow for sparring to occur between participants who are of equal size and strength so as not to allow room for discouragement from the smaller student who struggles against a much older and much heavier sparring partner.

Wrapping it all up

In summary, the process of implementing a kid’s jiu jitsu program curriculum at the Alliance Korea gym required a wide degree of theories and concepts. As the educator and curriculum author, it was required of me to apply these theories and stratagems efficiently and effectively and be cognizant of the factors, areas, and remedies for any misalignments in the instruction and internalization of the curriculum.

While perfect alignment across all components of a curriculum is ideal, practically speaking such a goal is not attainable due to uncontrollable factors and variables.

I hope this whole discussion has helped clarify some of the often vague or unseen factors in how to improve a curriculum. The misalignments of the various curriculum types are, frankly, a never-ending struggle to manage. There simply is no such thing as perfect alignment, which means that curriculums are always in a state of needing analysis, adjustment, execution, and then you repeat it all over again.